Bury the Chains by A. Hochschild

In all my reading last year, one story stood out from the rest. The telling was serviceable, but the tale itself fully deserves Alexis de Tocqueville’s accolades, “absolutely without precedent…if you pore over the histories of all peoples, I doubt you will find anything more extraordinary.” P.1

Nothing I could write here would add much to the content below. But the reason I excerpted at such length is this serves as an existence proof that some small number of committed humans can reshape the world impossibly, then inevitably, then, if they have done it right, anonymously. It is remarkable too, how much of the 19th century move/countermove involved will feel contemporary to anyone who has ever tried to get some collection of humans and institutions to do anything significant. I hope that the history below might remind anyone straining under some epically challenging moral effort, how much the frustration and unpleasantness involved is just the inevitable inertia and frictions of the physics of humans resisting change— independent of the justness of the movement. Finally, there may be lessons useful for those whose impossible quests don’t afford the luxury of 50 years of trial-and-error to resolve…

“At the end of the eighteenth century, well over three quarters of all people alive were in bondage of one kind or another, not the captivity of striped prison uniforms, but various systems of slavery or serfdom….The era was one when, as the historian Seymour Drescher puts it, “freedom, not slavery, was the peculiar institution.” p. 2

“Looking back today, what is even more astonishing than the pervasiveness of slavery in the late 1700s is how swiftly it died. By the end of the following century, slavery was, at least on paper, outlawed almost everywhere. The antislavery movement had achieved its goal in little more than one lifetime.” p.3

“For fifty years, activists in England worked to end slavery in the British empire. None of them gained a penny by doing so, and their eventual success meant a huge loss to the imperial economy. Scholars estimate that abolishing the slave trade and then slavery cost the British people 1.8 percent of their annual national income over more than half a century, many times the percentage most wealth countries today give in foreign aid.” p.5

The actions of small numbers of resolute individuals:

“An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man… All history resolves itself into the biography of a few stout and earnest persons”– Ralph Waldo Emerson p. 90

“Samuel Taylor Coleridge called him, “a moral Steam-Engine…””p. 89

“If there is a single moment at which the antislavery movement became inevitable, it was the day in June 1785 when Thomas Clarkson sat down by the edge of the road at Wades Milll….If there had been no Clarkson, there would still have been a movement in Britain, but perhaps not for some time to come….the Quaker’s antislavery committee had been unsuccessfully trying to ignite such a movement for two years, and Granville Sharp for two decades. It would take Clarkson to bring it into being, and his contemporaries recognized him for this.” p. 89

“”Coming in sight of Wades Mill in Hertfordshire, I sat down disconsolate on the turf by the roadside and held my horse. Here a thought came into my mind, that if the contents of my essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities to their end.“” p. 89 (June 1785)

“If we were to fix one point when the crusade began, it would be late afternoon of May 22, 1787 when twelve determined men sat down in the printing shop at 2 George Yard, amid flatbed presses, wooden trays of type, and large sheets of freshly printed book pages, to begin one of the most ambitious and brilliantly organized citizens’ movements of all time.” p. 3

“On June 7, 1787… the committee officially became the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.” p. 110

“Just as abolitionists were the prototype of modern citizen activism, so the West India lobby was the prototype of an industry under attack.” p.160

Countermoves of the opposition:

— lobbyists

“we do not know how much the [West India Committee] lobby spent all told, but the amount was substantial. By one estimate, the city authorities of Liverpool alone dispensed more than £10,000— the equivalent of $1.4 million today— and we know that the West India Committee paid £4,400 to a single lobbyist for three years’ work.” p. 160

—euphemism

“One of its first impulses was to consider “cosmetic changes.” “The vulgar are influenced by names and titles,” suggested on proslavery writer that year. “Instead of SLAVES, let the Negroes be called ASSISTANT PLANTERS; and we shall not then hear such violent outcries against the slave-trade by pious divines, tender-hearted poetesses, and short-sighted politicians.” p. 160

— public slander/private harassment [of Rev. James Ramsay], p. 111

“His enemies sent him packages of stones from the West Indies, because under the prevailing postal system, charges were paid by the recipient.” p. 111

— partial regulation [skirting the fundamental issues and tradeoffs]

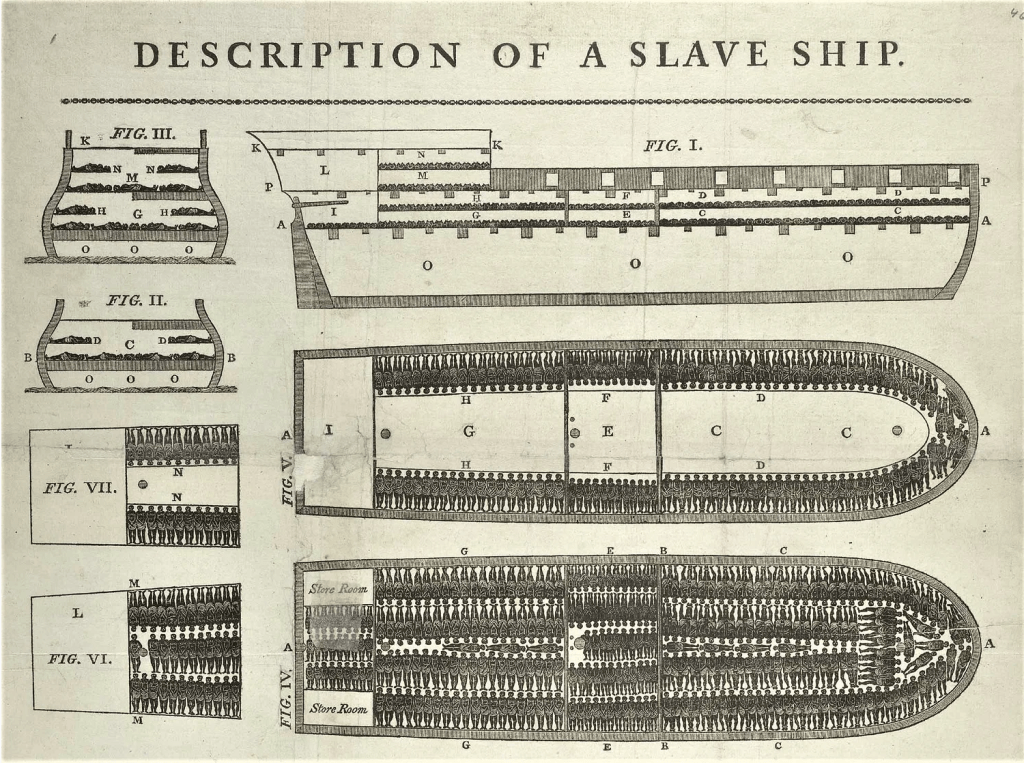

“One slavery-related bill did pass Parliament that year [1788]…. Dolben introduced a bill limiting, according to the ship’s tonnage, the number of slaves it could carry and requiring every ship to have a doctor as well as keep a register of slave and crew deaths. The abolition committee feared it would establish, as one member put it, “the Principle that the Trade was in itself just but had been abused.” Nonetheless, this was the first British legislation if any kind to regulate the trade.” p. 140

– nationalistic catastrophizing

“Angry Liverpool ship owners sent a rival group to lobby against the bill. “God only knows what will be the consequence if the present Bill is passed!…It may end in the destruction of all the whites in Jamaica,” wrote Stephen Fuller, London agent for the island’s planters.

“In his maiden speech before the bewigged lords in their red and ermine robes, he called himself “an attentive observer of the state of the negroes” who found them well cared for and “in a state of humble happiness.” Above all he parroted the abiding national belief, elaborated with less boorishness and greater refinement by other proslavery legislators, that the health of the navy, the merchant fleet, and the Caribbean colonies all rested on the slave trade; remove that one vital link and the empire was gone.” p. 187

– do-gooder dismissal

“The Lord High Chancellor scored the measure as the product of a “five days fit of philanthropy.””

– lying/nonsensical claims

“An exasperated Dolben mocked the Liverpool ship owners who claimed that “the ships most crowded were the most healthy” and that “the time passed on board a ship, while transporting from Africa to the colonies, was the happiest part of a negro’s life.” If this were so, he challenged them, why not take the voyage themselves, in “dangerous storms and perilous gales, rolling about with shackles upon them, in their own sickness and its consequences,” and then come address the House “after experiencing these extraordinary proofs of happiness”?

Weakened by amendments and often to be evaded in practice, the Dolben bill finally passed. p.140″

– competitive whataboutism

“Mild as the bill was, abolition agitation spread horror in the slave ports. “to abandon [the trade] to our rivals the French would stab the vitals of this nation, as a trading people,” one resident of Bristol wrote to a newspaper, “and leave our posterity to be in time Slaves themselves.” p. 140

“if Britain were to give up the trade, he asked, addressing a question on all minds, wouldn’t France simply take over the business? A this point, “a cry of assent being heard from several parts of the House,” Wilberforce declared that the same could be said of any evil. “For those who argue thus may argue equally, that we may rob, murder, and commit any crime, which anyone else would have committed, if we did not.” p. 161

—delay tactics

“The slave interests deftly outmaneuvered him. The insisted that the massive Privy Council report [850pg.]— which most members of Parliament had, of course, not even read— was not enough; on such an important subject, the House of Commons must exercise its historic right to hold its own hearings. A convenient excuse for uncertain M.P.s to delay taking a stand, this argument carried the day. Without protest, the gentlemanly Wilberforce, who always acted as if his opponents had only the best of intentions, consented. As Clarkson put it, the whole question was thereby, maddeningly, “by the intrigue of our opponents deferred to another year.” p. 162

—false colors, incrementalism

“Dundas began by declaring himself in favor of abolition, at which point the spectators looking down from the gallery must have felt their spirits rise. He then went boldly further and declared himself in favor of emancipation— but in the far future, he added quickly, and after much groundwork and education. Dundas’s speech signaled a moment that comes in every political crusade when the other side is forced to adopt the crusaders’ rhetoric: the factory farm keeps harvesting, but labels is produce “natural”; the oil company declares itself pro-environment, but keeps drilling. Dundas had called himself an abolitionist, but he asked that abolition be postposed. To the abolitionists dismay, he introduced an amendment that inserted the word “gradually” into Wilberforce’s motion to end the slave trade.” p. 232

“Dundas’s “gradually” provided exactly what the timid majority of Commons needed: a way to end a divisive national controversy, to look enlightened and responsive to popular will— and to make no immediate changes. The gradualist proposal passed, and after more debate, the House set 1796, four long years hence, as the date when the slave trade was supposed to end.” p. 233

— asserting self-regulation

“The society’s “gradual” nature, however, bogged it down…Not feeling under much pressure, Parliament merely passed some vague resolutions about such matters as encouraging marriage and religious instruction for slaves and ending the whipping of women. Responsibility for turning these suggestions into law was left in the hands of Caribbean island legislatures, which of course did nothing. The West India Committee promptly drafted its own lofty-sounding code of similar recommendations— an early instance of something familiar today, when an industry tries to fend off government regulation by proclaiming it can regulate itself. Planters ignored these guidelines as well.” p. 324

Effective moves of the movement

— leadership with complementary skills

“In Clarkson, the movement had an inspired organizer; in the Quakers, a network of dedicated activists; in Wilberforce, a parliamentary spokesperson of great respectability; in Granville Sharp, a venerable father figure, even if he made people’s eyes roll when he rattled on about frankpledge. Until now, though, what the abolitionists had lacked was a first-rate thinker who could figure out how, within the confines of Britain’s tradition-bound, half-democratic political system, they could transform into law the great reservoir of public opinion that—they hoped— was still on their side.” p. 301

— data vs myths

“He wanted to destroy for good the myth that the trade was a useful nursery for British seamen. By the time he was done, “in London, Bristol, and Liverpool I had already obtained the names of more than 20,000 seamen…knowing what had become of each.” p. 117

—heroic evidence gathering

“for three entire weeks Clarkson searched for one key witness, a former shipmate of his brother John, who was reportedly willing to speak about British expeditions in heavily armed canoes that traveled up the Niger River delta kidnapping slaves. Such testimony would refute the slave ship captains who maintained that they acquired their cargo only from African dealers, buying people who were already slaves. Methodically boarding vessels in six ports across southern England, Clarkson worked his way through 317 ships— some three quarters of the Royal Navy. Finally to his “inexpressible joy,” he found his man and returned to London with him and five other witnesses in tow.” p. 189

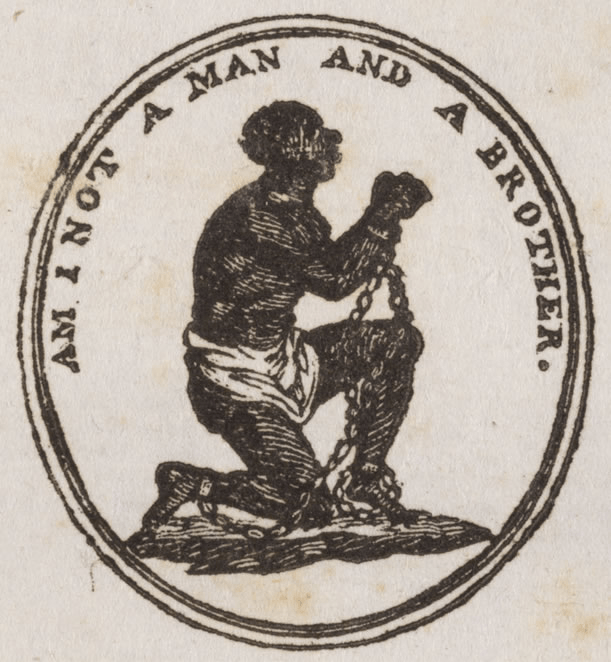

—spreading memes

—rebuttal

“He began by taking the “gradualists” at their word, that they favored abolition, and then one by one showed how each of their points was a better argument for ending the slave trade immediately. He mocked the idea that if British ships stopped carrying slaves, other countries would take over: Where would the get the ships? Where would they get the capital? And how could anyone expect France to increase its slave trading while desperately trying to put down the the St. Domingue rebellion?” And as for the trade itself, “How, Sir! is this enormous evil ever to be eradicated, if every nation is thus prudentially to wait till the concurrence of all the world shall have been obtained?…There is no nation in Europe that has, on the one had, plunged so deeply into this guilt as Great Britain, or that is so likely, on the other, to be looked up to as an example.”

— distillation of evidence

“At the committee’s request, Clarkson had taken the 648-page distillation of testimony [1700 pg.] before the Commons and further boiled it down to a quarter of the size. He then took to the road to distribute these books throughout England and Wales, traveling more than six thousand miles “by moving upwards and downwards in parallel lines…of almost incessant journeyings night and day.” To everyone’s surprise, this condensation of a condensation would become probably the most widely read piece of nonfiction antislavery material of all time.” p. 196

“The argumentative political pamphlet was very familiar to Britons, but this book was something different. in its carefully selected excerpts from documents and eyewitness accounts— illustrated, of course, with the famous slave ship diagram— the Abstract of the Evidence was, although the term did not yet exist, one of the first great works of investigative journalism.” p. 198

“In 1802, in The Crisis of the Sugar Colonies, he [James Stephen] used the St. Domingue revolution as an argument against slavery. Recalling the costly British military disaster, he correctly predicted the same for Napoleon’s armies. Britain’s islands in the Caribbean, filled with slaves ready to rebel and with climate and terrain difficult for European troops to fight in, would, he assured his readers, prove to be a huge drain on national resources. Addressing a war-weary country, he presented himself as a clear-thinking realist, speaking ‘not to the conscience of a British Statesman, but to his prudence alone.” His arguments were practical and impeccably patriotic; his loathing of slavery was kept carefully under wraps.” p. 302

—Seizing opportunity from changing landscapes

“One development did offer the abolitionists some hope. In contrast to revolutionary France that had formally liberated its colonial slaves in 1794, the France that Britain was fighting at the beginning of the 1800s was, of course, trying to restore slavery. Paradoxically, the archenemy Napoleon had thereby opened up some political space for British antislavery forces: they could associate abolition with British moral superiority.” p. 301

— Bureaucratic ninjitsu

“One day in early 1806, as Wilberforce was about to leave his house in Old Palace Yard for Parliament, planning doggedly to introduce another doomed abolition bill, Stephen called on him to suggest and help draft something different. It was a bill that banned British subjects, shipyards, outfitters, and insurers from participating in the slave trade to the colonies of France and its allies. In the short debate over this proposal, abolitionists barely mentioned the evils of slavery, and Wilberforce himself did not speak. The bill was hard to argue against, for how could anyone object to impeding trade with a country Britain had been fighting for more than a decade? But, this piece of legislation was more far-reaching than it appeared. A well-concealed secret was that many, possibly the majority, of the supposedly neutral “American” slave ships were in fact owned by Britons, manned by British crews, and outfitted in Liverpool. The only thing American on them was the flag. The new bill, the so-called Foreign Slave Trade Act, in the name of the war effort, would in effect cut off approximately two thirds of the British slave trade. Stephen himself, with his intimate knowledge of the maritime world, was one of the few people who understood the potential impact of the act.” p. 303

Victory…?

“In early 1807, a bill abolishing the entire British slave trade passed both houses of Parliament, the climax of twenty years of effort. Clarkson spent the day writing joyful letters to friends throughout the country. The abolitionists could still barely believe it when, a few weeks later, on March 25 as the clock struck noon, King George III officially gave his assent and the bill became law. The traffic that had taken more than 3 million captive Africans onto British ships for the middle passage was now reaching its end. This was not a case where the government provided leadership, commented the Edinburgh Review, but one where “the sense of the nation has pressed abolition upon our rulers.” p. 307

“to take part in the trade was later defined as a felony, and eventually, as piracy.” p. 307

“British warships eventually began stopping vessels all over the Atlantic, and troops of armed sailors boarded them to search for cargoes of slaves. In time as many as one third of Royal Navy vessels would be engaged in such patrols. With surprising swiftness Britain had gone, fit has been said, from chief poacher to gamekeeper.” p. 310

“but on the most dangerous doctrine of all, immediate freedom for slaves, the leading antislavery figures remained conspicuously silent. West Indian slavery was bound to disappear, they continued to believe, if the trade was completely stopped all countries…what accounted for this wishful thinking?” p. 322

“Without newly imported slaves, owners knew,… they had to “encourage healthy propagation.” And so they began offering their slaves better diets and treating them somewhat less harshly; they also installed improved sugar mill machinery including a relatively simple safety screen… as a result of such changes, slave birth rates were increasing.” p. 323

“Even Clarkson, who should have known better, believed that “Emancipation, like a beautiful plant, may, in its due season, rise out of the abolition of the Slave-trade.” But as the years went by, it became painfully clear that nothing was rising out of the ashes except more slave-grown crops.” p. 322

Reprise:

“[Parliamentary] Reform and the revived antislavery movement were two of the events that would help doom British slavery. A third was the insurrection in the crown jewel of Britain’s Caribbean colonies [Jamaica].” p.344

The debate lasted more than three months, making this session of Parliament one of the longest in memory. As emancipation began to seem even more likely, the West India lobby shrewdly switched its target, mounting an aggressive fight to be paid for the human property that, it appeared, might be taken from them….

The triumph came at last when the emancipation bill passed both houses of Parliament in the summer of 1833….tarnished by the price attached, for Parliament voted to the plantation owners £20 million in government bonds, an amount equal to roughly 40 percent of the national budget then, and to about $2.2 billion today.

To further soften the blow to planters, Parliament decreed that emancipation was to happen in two stages. The slaves would become”apprentices” in 1834, obligated to work full time for their owners, in most cases for six years, without pay. Only after that would they be fully liberated…

As a result of pressure on both sides of the ocean, the term of six years was shortened to four.

The real victory, then, came on August 1, 1838, when nearly 800,000 black men, women, and children throughout the British empire officially became free.” p. 347-348

Misc. excerpts

“the world rushes headlong without looking, as if summoned to the bedside of the dying.” p. 110

[Wilberforce’s election]

“On his twenty-first birthday, he threw a huge feast in one of his family’s fields– an ox roasted whole, a bonfire, many barrels of ale– then passed out over £8,000 (over $1.2 million in today’s money) among the voters in his Hull constituency, as was the custom of the day, and took his seat a few weeks later.” p. 125

“he and his supporters kept a record book listing each voter with an income of £100 or more a year, and information such as “whether he likes the leg or wing of a fowl best, that when one dines with him one may win his heart by helping him.” p. 125

“Britain sent more soldiers to the West Indian campaign than it did to suppress the North American rebels two decades earlier, and the war cost far more lives.” p. 281

“in Edmond Burke’s memorable phrase, it was like fighting to conquer a cemetery.” p. 278